Infertility, miscarriage, infant loss all part of Austin mom’s parenting story in new book

[ad_1]

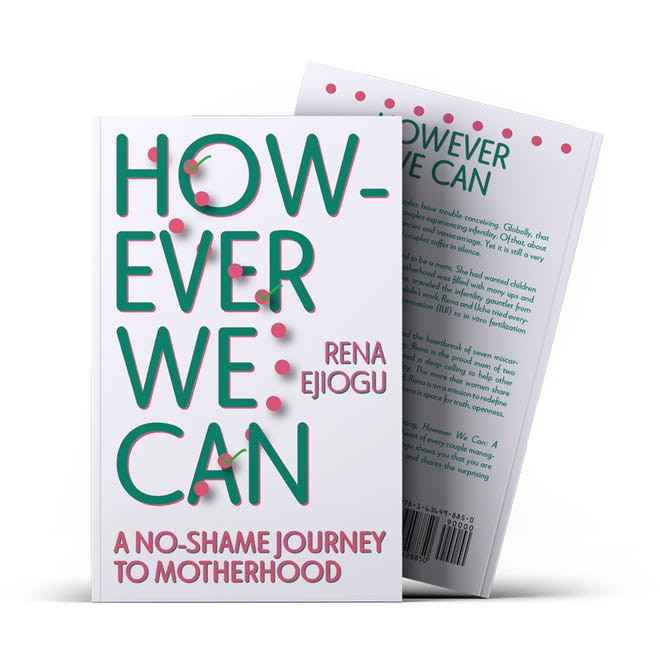

Rena Ejiogu’s nine-year journey to complete her family is detailed in her book “However We Can: A No-Shame Journey to Motherhood”.

The 40-year-old mother from Austin explains all the steps she and her husband Uche Ejiogu took to have their two children, Anson, 8, and Arisa, 4. Those steps included seven miscarriages, including one after 18 weeks, and one failed surrogacy. Along with the medical steps, she talks about the difficult emotions and heartache that didn’t end with the birth of her first child.

The book was written at the beginning of the pandemic, she says. “When the world collapsed, I had no reason to be silent,” she says. “I wanted to make sure that all women, men, and couples going through infertility and loss are not alone.”

She tells her own story, but also explains the procedures she went through and what she experienced in the process. She wanted the book to be helpful to both people with infertility and those who know who it is and want to understand it better.

Ejiogu writes about meeting the boy she would later marry in high school and was drawn to him, but nothing came of that until they met again in their twenties.

At the age of 28, they married and tried to raise a family. They thought it was easy. Ejiogu assumed that she would be like her sister, “who looked at her husband and got pregnant”.

Nobody had ever spoken to her about the fact that her irregular menstrual cycle was a problem.

A year after the trial, they first tried homeopathic supplements and tried to record their cycles.

She honestly writes that sex has become a robot. “We had to do it because we wanted something, not because we wanted each other,” she writes.

The right time:Snow and ice can’t stop the in vitro fertilization cycles at the Texas Fertility Center

They made their first trip to a fertility clinic. It felt cold and depressing. She felt like a number. They ran test after test and came back with “unexplained fertility” as a diagnosis. She writes about the hope that they would find something, anything that could be fixed.

“If we don’t know the cause of the problem, it’s hard to fix,” she writes.

All of her tests, her blood counts were normal.

You have tried everything, including following bad advice. Ejiogu was a dental hygienist and her patients would tell her things like “The reason you won’t get pregnant is because you are not 16 and have a one night stand”.

So they tried going to a bar and pretending they didn’t know each other and then picked each other up again.

That did not work.

People would also tell her to just relax, she says. “Relaxing was a trigger word,” she says.

“The whole situation is stressful, whether you realize it or not,” she says. But she didn’t see it as stress, she saw it as something she had to go through.

All around her, people got pregnant and had babies. At first she could be happy for her, but over the years “I got mad,” she says. “It took me longer to process the message. … I went home and yelled my eyes out for days. I saw people I didn’t know and annoyed them. ”

People also nudged her to start a family without realizing that she was desperately trying to do just that.

She describes being on her mind a lot. “Nobody knew what I was going through … I was the Queen of Jekyll and Hyde,” she says.

Infertility Costs:If infertility is a disease now, why isn’t it covered by insurance?

They went through all of the infertility treatments step by step that led to more invasive and expensive procedures until they came to in vitro fertilization.

Doing IVF “was a very lonely time,” she writes. Nobody really talks about their experiences because fertility treatments are stigmatized and so is the fear that if you talk about them you won’t get pregnant. “The messaging is relentless,” she writes.

The first attempt did not last, but the next, although she lost one of the two implanted embryos.

The second embryo survived and through a successful pregnancy their son Anson was born. “I welcomed every single pregnancy symptom I had because it was so difficult for us to get pregnant,” she writes.

However, the birth was a traumatic experience. She vomited repeatedly. Anson got stuck and had to be sucked out. In the end, she had 40 stitches and a prolapsed bladder.

Ejiogu felt that her family was not complete. To them, a family was more than a baby.

When Anson was one and a half years old, they implanted the remaining embryos from her first round of IVF and she miscarried.

She writes: “The more miscarriages I experienced, the faster I went from ‘Oh, dang’ to utter despair. I was frustrated and angry. Any failure to get pregnant and carry would cost a little piece of me every time. ”

They decided to have another round of IVF and she became pregnant. Eighteen weeks after pregnancy, she felt a bang. Her cervix has expanded completely, “and there was nothing they could do,” she writes.

She had to free Ashtyn. Since Ashtyn was not considered viable, the loss was labeled a miscarriage, but it felt different to Ejiogu. She had felt Ashtyn very much before she died. She gave birth and held her, knowing that she looked very much like Anson as a baby.

They still honor Ashtyn by planting purple flowers in front of their house. It is the color that they have always associated with her. They light a candle on her birthday and on October 15, the commemoration day for pregnancy and infant loss.

The months after Ashtyn’s death were tough because people knew she was pregnant but they didn’t know what had happened. Her milk also came just about the time Ashtyn should have been born.

Even when people found out what happened, they would say insensitive things like, “Are you not feeling better yet?”

“You don’t wake up here and everything is kosher,” she says. “It will be with us for a lifetime.”

They decided not to let Ejiogu get pregnant again and found a surrogate mother, which was complicated because her embryos were in Canada, which is where she and Uche are from, but by then they had moved to Texas.

The embryos were not allowed to be taken across the border, which meant the surrogate mother had to be in Canada. Canada has much stricter surrogacy regulations, including the fact that surrogacy cannot be paid for. Her surrogate mother, who was her sister’s friend, turned to her after hearing of Ashtyn’s loss.

Medical experts:Austin doctor saves babies from blindness as world expert on premature retinopathy

Surrogacy was another round of worry and embryos that were not accepted. And then Ejiogu unexpectedly got pregnant naturally, and the surrogate mother didn’t.

Daughter Arisa was born by caesarean section because the birth had already damaged Ejiogu’s body.

Ejiogu later had surgery to treat a herniated bladder, uterus, rectum, and cervix, and then eventually had a hysterectomy.

“The birth broke my body,” she says, “but I have great kids. They are so funny. They drive me crazy in the best possible way. They taught me patience.”

As soon as Arisa was born, Ejiogu knew she was done. She no longer feels the strong longing for a baby. She can hold a friend’s baby and wants to give it back.

The loss of Ashtyn is still felt by the feeling that something is missing. She’ll drive and look at her kids in the back seat and think, “There should be three.” And she’ll wonder what life would have been like if Ashtyn had made it full-time.

Ejiogu estimates they spent at least $ 80,000 on fertility treatments to support their family. It could have ruined their marriage, she says, but “it brought us closer to us. … If we could go through this, we can go through anything.”

They learned to give each other space when they needed it. They learned to talk about what happened and not to blame. “I told him, ‘I’m sorry my body isn’t working,'” she says. “He was upset. ‘It’s not you, it’s us.’ We always work with a we mentality. “

She learned to live in the now and not go down the rabbit hole of “what if that doesn’t work, what’s next”. She learned to do whatever it takes to focus on her own mental health.

Specialized care:Dell Children’s Hospital Opens New Specialty Pavilion With Fetal Care Center, More Family Services

She also learned the importance of having supportive people who were simply good listeners. “It was a safe place,” says Ejiogu of a high school friend with whom she came back in contact shortly after Ashtyn’s death. One thing she said to Ejiogu was that she might not understand or didn’t know what to say, but she would just listen. “It got me talking,” says Ejiogu.

The book turned out to be part of her own healing. “It was very therapeutic and healing to bring the details out the way I did, to be so open and vulnerable,” she says.

She describes herself as a Type A personality, a daredevil personality. She endured a lot and didn’t really deal with the trauma of it until she sat down to write it.

“I was really good at dividing my emotions and putting on a brave face,” she says. Now she understands the importance of telling the story of infertility in order to talk about it.

[ad_2]